MARSEILLE

A mere five minutes later, I’m in transit. The laid-back nature of southern France.

I’m on my way to Paris-Orly. Then I’ll be leaving Europe and returning to the United States for the first time since 2011 and 1994.

How much has America’s heartbeat changed? What about its fears? Its hopes?

Boarding.

PARIS-ORLY

The landing is like any other at Parisian airports: a mogul course, sliding on ice. My stomach does a somersault. Old airport, no transit area. Travelers who’ve lost their way. Huge suitcases. The wait at the security check is twenty minutes or more.

I take the Fast Track and feel like Georg Clooney. It takes me only three minutes to pass through.

An American woman reads Harlan Coben. Then she takes out her Samsung and enters “Dr. V, Botox” in her calendar.

The art of building a bubble around oneself.

Boarding.

P.S.: No one knows why you have to sit in a plane air-conditioned to a chilly 60 degrees.

NEW YORK

The plane is two hours late. A final taste of Europe in the inflight meal: Breton cookies; sauvignon from the Gascoigne; framboise dessert avec du Cognac.

A quick jolt of adrenaline. Now what?

Stand in line! Where are you arriving from? What is your purpose in visiting the United States? When will you return?

All ten fingers scanned. My pupils too. The officer seems unimpressed by my answer that I’m here to promote my new novel. She stamps my passport without another word. No cell phone check. U.S. Customs: Do you have anything to declare? Six leather friendship bracelets. “Like these.” He doesn’t spare them a glance. I’m waved on.

“No one does,” he says. “You’re the first.”

“I keep out of politics,” Jean-Marcel says. “You have to be a politician to understand politics. He’s the president now…” My driver pauses, shrugs his broad shoulders, “…and a few years from now, it will be someone else.”

“Yes,” I say. Washington is irrelevant to Jean-Marcel’s survival. “Tell me about your book,” he says. He also likes to go rhumba dancing. And salsa. Manhattan glows golden in the evening sun.

8:00 pm local time. Empire Hotel. For me, it’s two in the morning. I wander down Broadway, past Lincoln Center. Smoking is only allowed outside the park.

Dinner at Clarke’s. Like everywhere in the world, the waitresses tend to the woman traveling alone with motherly care. The fifteen-dollar glass of Laphroig whisky is three stories high.

It’s 10:30 pm, four-thirty in the morning, my time, when I fall into bed. I leave the window open and turn off the air-conditioning. I sleep in stages, deeply and as motionless as an old rock.

I have cherries from Washington for breakfast. The season is almost over. One pound of cherries costs five bucks.

I share them with a homeless couple just outside Central Park. They are smoking shit. It’s Gay Pride today, they tell me. ABC is broadcasting the parade for the first time in 37 years.

We talk for half an hour. I like his skull rings.

Filter bubble on. I hear Sunny in my head. I damp my emotions. Make myself friendlier. I shared the rest of my cherries with a beggar on Broadway. He was standing in front of the book-filled entrance to Penguin Random House and asked whether I was going to finish the fruit. I offered him the bag so he could reach inside. He held up his hands. “You don’t want me to do that…” But they were only a little dirty. Before he had time to feel ashamed, I shovel a pound of cherries into the open bowl of his cracked fingers. I carry his smile along into my filter bubble.

Another beggar stands in front of the train station. Or maybe he’s just a normal person looking for a handout. Who can tell? No cherries this time. Cigarettes. I give him my last three Gauloises, imported from France.

“Bien sur, Madame,” he says and pockets them without moving. We don’t talk about Trump. I’d like to. At the same time, I’d rather not.

It’s obvious that the people who work in the book industry—“the business of hope,” as my publisher likes to say—find Trump unsettling. They cannot explain how this terrible joke could have come true, and how often they have to deal with European colleagues who torment them with this reality. It would be like people reproachfully asking you or me—over and over again—why “the Germans” keep voting for AfD (the ultra-right “Alternative für Deutschland”-party). Even though “the Germans” do not, in fact, “keep voting for AfD.”

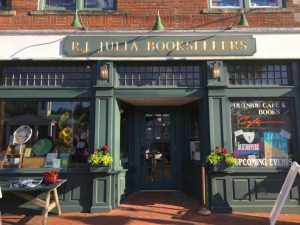

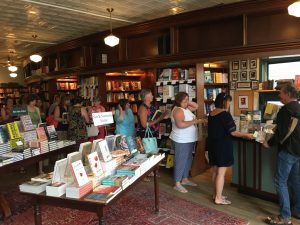

In three hours, I’ll be on my way to Madison and R.J. Julia.

MADISON, CONNECTICUT

Rebecca’s Amtrak tutorial yesterday on the ride to Madison, Connecticut — a town of facades that look like decorated cakes—should have been sufficient preparation. And yet, I react like a typical European. To put it mildly. With irritation, you could even say. And gratitude for Deutsche Bahn.

Soldiers on patrol in Penn Station. The announcement for the departure platform comes only five minutes before the (planned, hoped for) departure (at the earliest). On huge panels, before which a crowd of what feels like thousands is lurking, ready to make a mad dash. Or at least to avoid being the last person in line. Trains to New Orleans are traditionally six hours late.

Bam! Platform 12W! Hundreds of travelers with suitcases the size of coffins squeeze their way through the bottleneck to the escalator. Whoever gets to the bottom first can pick a seat in the mile-long iron dragon, which will slice through the horizon, glittering in the sunshine, at a speed of 150 miles an hour. Everyone else grabs the free seats. No reservations. The air conditioning system is set to a wintry temperature.

Only a few people watch movies or listen to music with earplugs. Instead, a cacophony of children’s games, TV series and movies blares from iPhones. Business Class is half filled with legislators murmuring into their phones, commuting to Washington. A New York senator poses for a photo with his fans. I discreetly move out of the picture. If he only knew.

How many years have I been writing now? Twenty-six, if you count the years I’ve been published professionally. Thirty if you add on the discreetly revised journals that I wrote at 13, 14. A fictional life, because my real one was limited, with me full of longing.

Suddenly, I feel weak, in pain, agitated. It was such a long journey. A very long way. Thousands of tears. The Little French Bistro was where I found my voice. I’m struck by the fact that it took seven, eight, nine years for my voice to be heard. Here, before these people, who are so different and yet so similar. Culture, politics, everyday life: they are so different. We hold Trump in contempt. We should mind our own business.

But the feeling—to love, to be hurt when we are not loved; to grow older, to ask ourselves: is this where I’m supposed to be? What have I done with my life—is this really me?—female moments. Love of self; being alive, truly alive: all these things cross something as trivial as a national border. They meld us together. Woman and woman and woman. Across age, religions, occupations, appearances, beyond everyday life.

Books. The Résistance.

At the end of the long, really, really long signing line (I’m not used to seeing everyone buy a book?!), a woman comes up to me. She reminds me of Diane Keaton. We speak French. She will fly to Europe next week. She strongly suspects that she will have to apologize for Trump to everyone she meets there. “Il est un…” she begins. “Asshole?” I suggest while she supplies “Grand con.” Absolute idiot. We toss four-letter words back and forth.

“Excuse our French” I tell the bookseller. We all laugh, liberated.

Diane Keaton’s doppelganger says she’s embarrassed to go to France as an American. She feels a desperate need to explain that America is not like that. It really isn’t. The bookseller will say the same thing.

She talks about colleagues in Trump Country, where he won the majority of votes, who placed more anti-Trump books than usual in their shop windows on the day of the Pussyhat Women’s March. Who set up display tables under the slogan: “freedom of speech is democracy.” Customers then complained to the management. Some of them boycotted the stores. Because that freedom-of-speech idea—such anarchy. So political.

Incidentally, science fiction is hip (again). So are love stories without a happy ending.

And, indeed, Herman Koch.

"The book business is a real business of just hope.”

When I’m introduced, my work as an activist for women’s rights and author’s rights earns me more applause than the mention of my 35 translation.

Another visit to PJ Clarkes. Holly, Frances and my waitress are more delighted with the French cigarette I’ve secretly slipped under the bill than they are with the tip.br>

Later, after Frances has left, I watch a woman seated at a piano in the night, playing music on 62nd Street.

For the first time, I wash a shirt and a dress. Living out of a carry-on.

In the room next door, loud Americans (with boring stories) party until well past four-thirty in the morning and slam the doors. I consider yelling at them. Leave it be. I cry a little, sleep with silicone earplugs in my ears and the window open. The sun, rising five-and-a-half hors later, shines onto my naked belly.br>

Blues. New York, I already miss you. And I don’t even know you very well. As I leave the Empire to meet the brilliant Crown ladies at the Brasserie Cognac (the book business is female—complete with glass ceiling just below the executive level; Germany and the United States are similar in this respect), I turn over the sign on my hard-partying neighbors’ door.

From “Do not disturb” to “Please clean the room.”

I never claimed to be perfect.br>

The Amtrak train races through green countryside, over bridges and water, past bare ground and along highways with enormous transformer trucks, under a Stephen King sky.br>

The little girl has stopped screaming after two long hours, finally exhausted.

This evening’s venue: Politics and Prose, Washington D.C.

We are getting closer to the rumblings.

WASHINGTON, D.C.

It’s ten-thirty at night—after the show at “Politics & Prose,” which is perhaps the most politically uncomfortable bookstore in North America—and I’m standing in front of the brightly lit White House. A warm breeze dances around my bare legs. I’m hungry, but there’s nothing in a radius of ten blocks—not so much as a dim sum shop. I’m so tired, I might just fall asleep on the spot, leaning against a red cross-walk light post.

The Secret Service men (can you really call them secret when their agency name is emblazoned across their bullet-proof vests?) are mainly young, very young. Some circle the grounds on mountain bikes. They look me in the eye and nod as though I were somebody, someone that they know on her way home after work. I take a walk around the mansion. The white shirts that the young security lads wear under their dark vests and gun belts gleam in the darkness of the night. I am all alone on my walk, and I wonder where he’s sleeping in there. Whether he’s sleeping. What I’d do if I met him. And what purpose an encounter would serve (none, if I’m perfectly honest with myself).

More than ever before, I notice a kind of separation by skin color. The light-skinned people carry guns and work while seated at a desk. Those of dark complexion open doors and patrol perimeters. Or drive taxis and shuttles. At night, they sweep the floors of restaurants and takeout delis.

“Four blocks,” he says. It’s a safe neighborhood, he tells me.

“Fear is a bad advisor,” I reply, adding that I’m not afraid, except of people who arm themselves out of fear.

After I complete my walk around the House of Cards, I stand in front of it once more. Now I’m joined by a group of loud white Americans. I can’t help noticing that they’re all a few points past a healthy number on the body mass index. It’s as though they’re on a class trip to a barbecue, in the middle of the night. They take pictures of each other.

A small boy crows, “Look, dad! This is where our president lives!”

“Yes,” the father replies with pride.

They must be tourists, I think. And this boy will grow up in an America that resembles a dystopian version of the 80s in certain respects. In some all too important respects.

“If you see anyone running around Washington wearing a Trump hat, you can be certain it’s an American tourist.”

“Und doch,” says Katie, my hostess that evening. She thinks for a moment then adds, “Trump has torn down an invisible wall. He has paved the way for more and more celebrities to run for office over the next ten years. And they won’t know anything more about politics than he does.”

Mark Zuckerberg, the CEO of Facebook, has already hired his own campaign team. And potential candidates for POTUS have already made themselves heard from Hollywood.

Zuckerberg for President? Or perhaps Angelina Jolie?

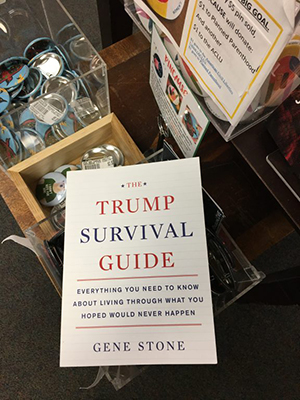

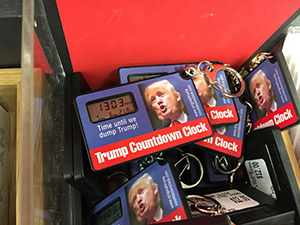

The bookstore devotes three long aisles to current affairs. A recording of super cool jazz is playing.

The store has a vinyl record section and a whole lot of politically themed giveaways.

Half the neighborhood is still hanging out here.

I regret that I never bought a “Pussy Over-Acting Figure” (I’m living out of a carry-on) or at least a survival guide to the Trump years. Not even a countdown meter showing how long America still has to put up with the man who washes up with “tiny hands” soap.

He’s talking about anonymous trolling and face news, sloppy communication skills, digital distance instead of analog proximity. Trump’s tweet storms but also the way people withdraw from the world and sit isolated in front of their computer screens instead of talking to each other, getting to know people.

Barry is the kind of person who makes friends easily. A glance, a smile, a question, a conversation. Tinder for the pre-digital age.

We smoke—Barry with his Pall Malls and me with my Marlboros. We flirt a bit, and by the time we part ways, he knows how the French say goodbye, including bisous—kisses on each cheek—and where he can find my books for sale.

He predicts that I’ll find the Pacific calmer than the Atlantic. I’d have liked to go swimming right then and there, with Mr. Waters.

With his laugh and his optimism—despite everything.

“No matter who is president, it doesn’t ruin your day. We need to stop acting as though we’re facing danger day after day. Life goes on.

So back to Politics & Prose. My impressions: Extremely mellow booksellers. I was apparently as exciting as a delivery of new “How to Protest” posters. That is: not exciting at all. I feel neglected but not exactly lonely. All around me are people who read. They constantly start conversations with me. I could spend the whole night there debating everything: hair, prejudices, the refugee crisis, Indian food, the price of Washington real estate, authors who lack the courage to engage in political debate, nice boys and bad girls.

And also to “nasty women” – the meme was new for me: During one of the presidential debates last year, Trump referred to Hillary as a “nasty woman.” He meant it as an insult, of course, but she decided to embrace it as a badge of honor. Afterwards, “I am a nasty woman” became a rallying cry for progressive women in the resistance to Trump.

The basement houses a café with free Internet access and regular neighborhood debate clubs. Upstairs, an author puts in an appearance (daily!), and most of them address political themes. I’m shelved in the feel-good section. Still, I’m the artist with the most dynamic performance the roughly fifty or sixty guests have seen and read in a long, long time.

How are you? Instead of the usual “Oh, I’m fine? What about you?” (which I find boring), I always answer with the truth, which astonishes most people. Occasionally, they respond by telling me how they are doing.

Over and over again, I have to talk about what I am reading, and I have a sneaking feeling that Washington may soon to receive a large delivery of novels by Véronique Olmi.

That night back at the hotel, Meredith asks if I’d sign one of my books for the Jefferson’s “Author in Residence” Club. They’ve quickly purchased a copy in my absence. The bookshelf contains the works of all authors who either have slept at the Jefferson, were introduced here or who appeared at Prose & Politics.

There are significantly fewer women than men.

But later she makes sure that I get half a bottle of Sancerre for the price of a single glass, along with a plate of pasta, in my room. I eat my dinner in the enormous bed, read The Dinner by Hermann Koch and fall asleep, practically fork in hand.

Five-and-a-half hours later, my alarm goes off, and for a moment, I can’t remember why I’m supposed to get up shortly after six.

Oh, right: Chicago. I notice how much I cling to the food and drink from “home.” How I cling to my “aerial roots,” so that I don’t come completely unmoored in the strange otherness, the other language, other rituals, greeting ceremonies, ways of dealing with people, invisible rules.

So that I don’t forget who I am. To avoid assimilating beyond recognition.

I think about the people who have fled or been driven from their homes. I think about their aerial roots, what they eat, drink, say, believe, their rituals and unspoken rules.

And although I’d never attempt to compare my situation to theirs, I can nevertheless understand why people hold so firmly onto something of their own in a foreign place—why it’s so necessary.

“Surveys have shown that public opinion of America has decreased markedly since Trump took office,” reports the news channel on the taxi ride to Reagan International Airport. “Limited version of the travel ban to take effect,” says the Washington Post. All cab drivers I’ve meet over the past few days have been to Frankfurt or Berlin. Who is going to replace Angela Merkel? they ask. One says: “We’re counting on her!”

I hold onto the feeling. Maybe fear and politics are deeply physical things. Or maybe I’m just overtired. There are hours when it’s like I’m wading through a dream. I’m not thinking, only absorbing, and I feel a wave approaching: overflow.

One in every 20 passengers is pulled out of the line and screened thoroughly. And yet, I wonder why all of them have darker complexions than, say, I do. Coincidence?

At Hudson’s Booksellers , Circle by Dave Eggers, the Google dystopia of a too smart dictatorship, is a perennial bestseller.

Veterans are allowed to board the plane before everyone else. Even before First Class. Their names are called out, and they’re thanked for their service, in the same unctuous tone one used to use for “Group A may board now.” Group Life Spent in the Military, you may board now.

Eleven am local time.

High above the clouds. Another 27 minutes before landing. Please return your trays to their locked positions. From now on, I’m seven hours behind Europe.

Lake Michigan gleams a shade of turquoise. Bill Young is already waiting for me. He lives three doors down from Hemingway’s childhood home and once hosted the French writer, Anais Nin —but that’s a story for another day.

Tomorrow. Later. Now.

CHICAGO

They rake the sand. I roll out of the too wide bed at 5:34 am after five hours of sleep and half a Corona beer in lieu of dinner, awoken by light and a burning desire to breath real instead of conditioned air. Joggers along the beach path greet each other with a nod. Lake Michigan, America’s biggest fresh water reservoir glistens, clear and a light shade of blue.

Chicago. The Blues Brothers sing in my head. Chicago, you’re just like New York, only friendlier, more warm-hearted, more luminous. Cleaner. And you have your own small sea at the foot of the skyscrapers, its horizon too far away to see.

And Donald Trump hates you.

From the bottom of his heart—although yesterday Bill Young speculated that Trump doesn’t have a heart. “Trump lacks empathy. Compassion. He is on the side of neither the Democrats nor the Republicans.

All Donald Trump cares about is Donald Trump.” If America had shown up at the polls—the entire electorate or even only 70 percent—Trump would not be in the White House. America didn’t want Trump.

But Bill was too tired of everything to vote. He dropped out of school, as did I, and then took jobs in bookstores. He opened one of his own and brought authors to Chicago. He invited Anais Nin a year before her death. Also Barack Obama and Joanne K. Rowling.

We pass tranquil hours driving around in his Toyota. Downtown. To Naperville and back again. Several hours, quiet conversations interrupted by comfortable, intimate silence. We tell each other things from our lives, from our souls. Our words will remain in the silence that filled the car.

Chicago. A man stands at the intersection in front of the Water Tower. He’s yelling: “Could anybody help? COULD ANYBODY HELP?” Startled, I turn around. “It’s been too long since I took a First Aid class.” That was my first thought. My second: “How come I’m the only one who turned around?”

Then I realize it’s one of the beggars. He’s yelling and waving a plastic cup around.

Later, after I’ve gone down to the lake for the first time, I’ll go back and give him seven dollars.

The same to the girl crouching on the other side of the street, curled into herself. She’s reading a book as she begs, leaning far over the pages. The city ebbs and flows around her, and no one tosses cigarettes onto the sidewalk.

I write the words in all the books with a blue felt-tipped pen. Stay safe.

I talk. Read. Answer questions. I’m given champagne. Word has gotten out that the author from Europe likes to drink during her performance. Once again, I blame it on jetlag. It’s midnight, my time, and I’m always tired, always fully awake at the same time.

What does the Naperville crowd of only 35 people know about Germany? What do they like? The delicious cuisine.

Schwainebrooten.

What about France?

Paris.

We talk about second chances, character development, landscapes of the soul. Reading my books, they tell me, is like being there in person. Like tasting the food, smelling the aromas.

Mary Ann quietly thanks me. She’s heard that I have a low opinion of Amazon. She doesn’t either. She sweeps an arm around Anderson’s.

This is what matters. She means the place, the women selling the books. Conversation. Browsing the shelves. I sign a pillar.

Not the one that George W. Bush immortalized. As did #44. Each president gets a number. So that no one forgets.

Even Bush wasn’t as terrible as Trump, Bill tells me. And that’s saying a lot. He despised Bush.

Aurora comes up to me and brings me full circle with Rachel Hildebrandt. Let’s plan to tell stories about real life.

Macarons are served later on. I get to pick out another book, and the doorman at the Drake greets me by my first name. Welcome back! He hugs me. I hug him back with all my might, as I always do. With everything I’ve got. He falls in love. I do not.

Europe slaps Google with a record-breaking fine. Google is the biggest employer in Chicago.

Trump hates Chicago because the city doesn’t love him. Because it mocks him.

A game of Frisbee on the beach. And rugby as well. Police officers patrol on quad bikes. A boy is playing the banjo. The Good Humor Man pulls his cart across the sand, bell ringing. No smoking on the beach. Fifteen bucks for a foot massage.

My alarm plays La Mer. The reading is over.

It’s time to return to the Drake, get up once again. Take a shower.

The morning sun warms me.

Just a moment, please.

Let me take a breath just for a moment.

And we’re off.

Addendum: How are you? It’s not a question but a courtesy. Like saying ça va? Like Schönen Tag noch. It’s not a good idea to respond by listing all your problems.

AUSTIN, TEXAS

7:33 am, local time. Waiting area at Gate 3, Frontier Airline heading for San Diego. Motown music at the airport. Security is relaxed.

75 degrees at 5:15 am when my alarm quietly sings La Mer. The temperature climbs every half hour. It’s 80 by 6:30 and still rising. The air is damp and thick. It’s like breathing through a wet handkerchief. Later, on the plane, the air conditioning will spray a mist of condensation. Disco fog. Smoke on the water. Like always, soldiers on active duty get to board before everyone else.

On my walk yesterday—from Capitol via 2nd Street, zig-zagging back to Ella’s hotel—I seek out the shade, like everyone else, even under the slimmest of trees. The streets, too bright under the burning sun, are empty. Anyone who gets the chance, ducks into the icy indoors. Many people leave their engines running in their parked cars. Air conditioners run at full blast—the one in the hotel hisses like the Orient Express, simulates a stiff breeze. I love it. Henning from Berlin meets me for a frozen yogurt. He’s an intellectual property attorney, naturally. Later in the evening, I will give a talk on authors’ rights in continental Europe at BookPeople. The audience will love it and envy the way we European authors retain control over our work—even beyond the grave. Copyright is weaker than authors’ rights.

I receive catcalls for the first time on this tour.

The first one comes after my interview for the Kirkus Review podcast, which takes place in a tidy little house.

Clay looks like Hugh Grant. He dresses like a Brit—not like any American I’ve met so far. It does my overtired eyes good.

Afterwards, I stand around in my blue-and-white Lauren dress, smoking, careful not to press too much air through that damp handkerchief. I look at the papier maché figures that someone hung up for a child’s birthday. They beat them with sticks until the fake skin bursts and candy rains down all around—just as a pickup truck rumbles past, the strapping sound of the SUVs here, which seem to get bigger all the time.

“Sexxxxx-yyy! Yee-haw!” a man calls out, honks and roars off. I decide to take it as a compliment. Kristen Holland, my hostess, laughs herself to pieces. She gave me cookies and apples to take along on my flight to San Diego.

Catcalls. I collect a whole range of calls downtown. Invitations to start a conversation. Unsolicited commentary about my appearance—all in that lyrical, drawn-out, American drawl. “Yeah,” they say instead of “yes.” Sometimes even “yah.”

I don’t find it unpleasant. I’m nearly 44, and someday the time will come when they say: “You can still tell how beautiful she used to be.” The silly things that people say, thinking they’re being semi-charming.

So I take comfort from Austin, in Austin, where the trucks still honk at my backside.

BookPeople.

Nice green dress, the cashier says. Maybe that’s the custom here, and we anxious Germans are just not used to people who notice when someone’s made an effort?

BookPeople is famous within the industry. It’s incredibly huge, with an incredibly diverse assortment. Author events every day.

They serve ice-cold sweet cider. Vince is here, as are Heidi’s translator friends. A woman plays me a two-minute message from her friend, Gailie.

Another has been reading The Little Paris Bookshop for four months. She’s on her fourth time through, always starting all over from the beginning. Rebecca’s amazingly warm-hearted mother, who beta-read The Little French Bistro, hugs me, and I’ve been adopted for a moment.

Nightlife in downtown Austin. I’m 14 and play skip-to-my-Lou. Lecture the poor bartender on the fact that his Muscadet has cork taint.

The night chirps around me, clings warmly to my skin. The city has come awake now at eleven-thirty pm — eating, dancing, cruising, promenading.

Not quite five hours of sleep.

When I reach San Diego, I’ll be eight (or nine?) hours behind Europe.

Europe, I’m living in your past.

You are my future.

I think about Stephen King. The story where the immediate past keeps get eaten away.

The Langoliers.

SAN DIEGO / LA JOLLA, CALIFORNIA

I’m lying on my bed at the rose-hued La Valencia Hotel — a room with a view.

I’m also in love. With five cities behind me, this is the first time that I feel so comfortable I’d like to stick around a while. Palm trees, ocean, French-styled patios, no excruciating traffic congestion. California.

The state where gluten is viewed with suspicion as the latest poison. Where no one smokes and every other bar is turned into a yoga studio.

Where I discuss Heraclitus, Hegel, Spinoza, the Big Bang, poetry and the difference between culture and lifestyle with a Persian cigarette vendor. Where people past the age of 50 miss driving the 12 miles to Tijuana without passing border control. Where they hang out at the beach, share a meal and simply enjoy life the way children do.

Where people in shops address me as “my friend” and where the Navy is everywhere.

I sign books for an hour, while outdoors the silky blue sky hangs low over the dry and simultaneously green landscape. The resort has to keep its lights off at night; nearby, an astronomical observatory peers with a thousand eyes deep into the endless expanse of space that envelops us.

Ladies’ lunch. The valets who park the really huge, white, gold and beige SUVs are barely older than 21; who has three hours of free time on a Thursday afternoon? Some of the clothing exudes discreet wealth. The earrings. The manicures.

At the same time, the women radiate an alert responsiveness. Straight talk. Constant eye contact as I sign their books. An astonishing number of them appraise my skin, ask why I look so young for a 44-year-old.

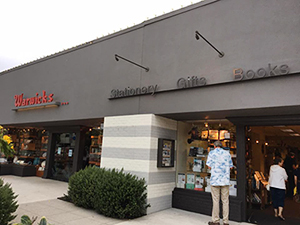

(At Warwick’s later in the evening, this question seems to be less intrusive than the desire to know my thoughts on the “current situation”—a Californian euphemism for Donald Trump, who is occasionally referred to here as “fucker,” even by frail, sun-wrinkled ladies.)

I love all these women. Their overabundance of warmth. Their willingness to be amused, under which lies a crystal-edged clarity. These are women who possess an inner strength, a purposefulness. This gathering, I have to admit, is a shining star on the entire tour. Eating, drinking, intelligent clowning around. In an exquisite setting with an understated, luxurious ambience and excellent service from staff who are warm, genuine and professional all at the same time.

Where in Germany would such a concept take catch on? In Hamburg, where the moneyed crowd hangs out? In Munich, where many a lady has enough free? Or would it not work at all? Maybe not in exactly the same way but with certain differences? Should we spend more time talking with our listeners instead of reading to them for 90 minutes? It took Elizabeth five years to make her idea take shape. I discuss travel bans with an Iranian literature professor named Poteh. We talk about the refugee crisis. He tells me that Germany is doing well in this area, better than other countries. He’s impressed by the way so many people volunteer their time to help out. Paris scares him. Terror. Scary. We arrange to get together in 2019. He wants me to give some lectures at his university.

I’m suddenly overcome by fatigue. I put down my cell phone. Tomorrow it’s Danville/San Francisco. Yeah, Ma’am.

6:58 am, local time. Woke with a start at 6 o’clock after sleeping like a log for five hours. The Pacific ebbs and flows. The sea lion family shares the first news of the day. Colonies of birds. The air carries the scent of ammonia.

Like nearly all the stores I’ve visited, Warwick’s is under female management. The crowd asked questions for a whole hour. The last one had to do with Trump. Grumbling from the audience. A chorus of “No!” Trump is too ever-present for their taste. He rubs them the wrong way. I decide I’m going to affirm democratic values. Anyone — man or woman — can be president. That is the American Dream. Democracy. To vote for whoever you wish to as well. And to tolerate other people’s opinions. To live with the outcome of an election — even a non-election — means living in a democracy. To get involved. Engage with others. Debate. Educate. This is precisely what our times demand of us.

Mary Lee, my hostess at Warwick’s washes my sweat-stained clothes.

I sign a hundred books. Next week, I’ll be among the top ten on the Indie List. A couple, both over 75, dance the Tango Argentino. It’s the first time I’ve seen this on my travels through this big and varied land.

“What does success feel like?” someone asks.

It doesn’t help with the writing. On many a sleepless night, it makes me feel like I’m spinning across a vast expanse of space. It helps me give to others: time, energy, taxes, gifts.

And also the freedom to do whatever I want — although the courage to do what I want doesn’t come from a bank account. It comes from the same source it always did. And sometimes I feel as despondent and contrary as I did at 15, when my first boyfriend said, “You want to be a writer? Really? What makes you think you have anything important to say?”

It was never about having something important to say.

I write to gain an understanding of life. It’s so intangible—our existence. Does it have a purpose? Does it make sense?

I always wanted to make a difference in my life. I wanted the random fact of being the four millionth person in the world to be more than a coincidence.

I will shine for some years. But in 200 years, or 400, I will just be another person in the nameless crowd. Like everyone. Like all of us. I find comfort in this. That way, I can exist in the here and now.

No one swims in the same river twice.

A Navy helicopter flies low over the Pacific. Slowly, I make my way back to the hotel.

How are you?

I’m tired. Wide awake. I swim through time, always moving forward and yet also backward.

SAN FRANCISCO

Danville, June 30, Healdsburg July 1, 2017

“The coldest winter I ever spent was a summer in San Francisco,” Mark Twain once said. The famous fog that envelopes the Golden Gate Bridge so decoratively is often ice-cold and can give unsuspecting tourists a first-class case of the sniffles.

The drive to Danville in heavy Memorial Day traffic stretches out to a good two hours, although the return trip later that night takes us only 40 minutes. On the way, we pass through San Francisco: Nob Hill—Snob Hill—the low-rent districts, which are not so low-rent anymore, now that the price of a San Francisco lease has shot through the roof.

As has the number of homeless people living on the streets—including the ones with a job, who work in hotels or on cleaning crews. Even teachers can no longer afford the city’s high rents.

Deirdre tells me that the people who work at Facebook, Google and other Internet companies are driving up the prices. They are inundating the once affordable neighborhoods, earn good money and take the virtual world rather than the analog one as their religion.

“Overpaid and under-civilized,” I murmur.

“You nailed it,” Dierdre agrees.

Amazon, Uber, Google—the New York native rejects these concepts because they destroy entire living environments and thoroughly undermine markets with a whole range of destructive consequences. Higher rents and empty stores. Anyone not in the high-tech business has to work longer hours for less money, and yet they suffer enormously under the impact of restructured analog living space.

We drive up a mountain, whose name I’ve forgotten. Maybe Twin Peaks. The city spreads out below us. The wind is so cold that my legs still have goosebumps a quarter-hour later. But my head, my heart, soars free; the view is unforgettable.

Then we head for Danville, driving through San Francisco’s “Golden Hills,” dried out by last week’s heat wave. 100 degrees Fahrenheit.

Rakestraw Books in Danville. Small, neighborly, cramped. Something about this city makes me feel sad and aggressive. Or maybe it’s the hysterical lady who accosts me and yells that I’m smoking in a handicap parking space. I point to the ashtray stand that is positioned right in this spot.

She tries to talk a man into making me move on, but he ignores her.

Rakestraw Books has organized a dinner event. The sun comes out as Heidi walks across the parking lot. She’s driven two hours to get here from Cupertino. What a sweetie! Sending you hugs from the Scarlet Huntington Hotel.

I talk for five minutes after the charcuterie is served and 25 minutes after the main course. Q&A before and signing during dessert. I barely have time to eat. Actually, there’s no time at all.

I notice with slight irritation that bookseller Michael fails to offer me water as I arrive.

Instead, he shoves me out the door to wait until everything is ready. He introduces me so briefly, it’s no more than just my name. And when I ask if I can have a glass of wine before my talk, he smiles and ignores my request. During my reading, he’s texting on his cell phone.

Everyone loves Michael. They describe him as creative and dedicated. To me, he seems like a little princeling in his paper kingdom, who feels nothing more than indifference toward me, the author from Europe. For the first time on the tour, I’m tempted to act the part of the petulant author and tell him just where he can shove his lukewarm “You were great” at the end of the evening.

But I don’t. Instead, I crank up the charm and mingle with the audience. From time to time, I pitch in and help clear away the empty plates and thus chat with everyone at all seven or eight tables. There’s a lot a laughter, plenty of questions. Patricia and I arrange to meet for tango lessons and wine tasting at her house in 2019. (Take that, Michael!) I become pen pals with Linda.

Nevertheless, it astonishes me to discover that details can hurt me, far more than open attacks. The glass of water not offered. The failure to say a few words about who the hell I am.

What did the audience appreciate the most?

When I told them that the idea behind The Little French Bistro was that life doesn’t end at 39 — a sexual, emotionally satisfying, love life continues at 40 and beyond. At first, some self-conscious clearing of throats all around. Then the roughly 50 listeners, mainly female, mainly on the far side of 55, 60, got into the groove. Spontaneous applause. “Yes!” rings out as once again I affirm that the desire for tenderness should not be restricted by the esthetic limitations of small-minded youngsters and the awkward conventions imposed on their elders.

San Francisco in the morning. I take the time to wander about for three and a half hours.

Music everywhere. Food from around the world: Indian, Chinese, French, vegan, gluten-free (of course). Sword swallowers. Bible salespeople. Alcatraz fans. Rickshaws. Cardboard figure of Donald Trump. Skateboarders. I’m the only smoker in sight.

Sunlight sparkling on water. Cable cars. I jump on the cable car heading for to “Fisher’s Dwarf.” The driver, Saul, glances over at me.

I tip Saul a dollar. He calls me sweetie, and from then on I get the seat with the best view throughout the tour.

Fisherman’s Wharf—Fisher's Dwarf. Beggars everywhere, relieving me of my spare change. I play around with old fortune teller machines, which crank out my future—nightclub hostess. Well, then.

I meet Jack and his two cats in front of the Ferry Building. One of them looks like “Commissaire Mazan”, a feline character from our Jean Bagnol noves.

Tonight I will finally drink a California Sauvignon — in my ballroom-sized hotel room (no minibar).

But first there’s the final stop on my tour: Copperfield’s in Healdsburg.

Deirdre says she’ll call first and she’ll remember to organize water and wine.

Sometimes Deirdre says things the same moment I think of them.

I’m looking forward to my return to Europe. I realize this. I’m looking forward to the coffee, the wine, the language, the music. Familiarity. Proximity to my inner self. My beach. The cliffs. The Breton sky. The majestic landscape. My novel.

And yet these days of travel will leave deep traces in my soul. I’ve brought along a few new dangerous thoughts.

More tomorrow.

I’m heading out now.

Final stop

Another 6 hours until my departure from San Francisco --> Paris.

6:40 am, local time.

I’ve woken up three hours earlier than I’d hoped, and I take the opportunity to chat on the phone with Anja Sieg, foreign correspondent for Buchreport. Local time in East Frisia, Germany: four-thirty. What do I find different about book tours in the United States? Does the audience value contact with authors? Is there anything the German book trade can borrow from the Americans? What impressed me?

This is what impressed me: The support offered by the readers. The desire to strike up conversations, ask questions—and good ones—craft questions, personal and political ones, questions focusing on specific aspects of the book. Not just global questions, such as “Where do you get your ideas?”

I was struck by the sense of empowerment and encouragement. Authors are valued for their courage and creativity. Not viewed as addled fools or grandstanders. And these are not just the people who happen to be in the bookstores. Cab drivers, doormen, people I meet at the airport. None of the smug condescension you sometimes encounter in Germany. Oh… so you’re a writer. Instead, an interested “what’s your book about?” And always the heartfelt expression of desire for your success. To have one’s work taken seriously — that’s what impressed me.

But, wait a minute. I haven’t told you about Copperfield’s Books in Healdsburg yet. I couldn’t have wished for a better end to the tour. The store’s two cats (one of them is name Pi, like Π) wind themselves between my legs. Lola, the cashier dog pants in rapt attention. Two of the booksellers tell me they wept with joy and excitement on hearing that Crown was sending the author of The Little Paris Bookshop to their store. Their words deeply touched my heart. I learn that half of Healdsburg has read The Bookshop, and the small, congenial gathering of perhaps 40 or 45 people are so approachable with their easy laughter and many questions, that they make this final stop a warm, highly personal and intimate end to my tour.

Later, when only five of us are left in the shop, it takes us less than ten minutes to work our way through the 200 books waiting to be signed, The “Neil Gaiman Assembly Line” goes like this: One person opens the book to the page to be signed. The next person shoves it under the author’s waiting pen. A third person pulls the book away and hands it to the final associate, who places it on the stack.

On a visit to Copperfield’s, Neil once used this method to sign 1,200 books in 32 minutes. A monster job!

On the drive to Healdsburg, Deirdre and I stopped at Book Passage, where Deirdre works. Once again, I signed books like a bat out of hell. One customer who happened to wander into the bookshop (which has its very own café!) stopped short, eyes wide. She got to have “her” author all to herself for five minutes. She reads everything she can find that mentions Paris or France. Americans love novels set in Italy or Paris.

And once again, I hear: “Oh yes! Berlin novels! How exotic!”

The recurring question: How do we get them translated? American publishers buy only 600 licenses to German books. Bestsellers. The proverbial eye of the needle.

You are so European!

I must be the only woman who smokes in all of California. And yet I’m loading up on far less nicotine than usual, which isn’t the worst thing in the world.

The states that have the worst problems with painkiller abuse and the most deaths related to opiate overdose, those are the states where Trump won the most votes.

Authors don’t get paid for their readings in this country. Publishers pay the travel and hotel expenses only for certain authors. Even more rarely do they provide media escorts, and so I am very, very fortunate. At the same time, I question the way a narrow focus on bestselling authors limits the book market and its diversity even more. There are two sides to everything.

This means that any (indy) bookstore can easily present an author every day (!). Many bestselling authors, such as Amy Tan, live in the Bay Area and will “drop in” from time to time. Some bookshops even organize two or three author events daily. Literature lunches. Afternoon meet & greets. A show in the evening.

People from the neighborhood come to these events, and they turn the store into something that is as much a local hangout as a commercial enterprise. This month alone, Book Passage will be hosting Salman Rushdie, Amy Tan, Karin Slaughter and Danielle Steel.

Amazon has bought the organic supermarket chain, Whole Foods. Deirdre wonders whether she can ever go shopping there again. By where else can she go? Amazon wants to roll out an online food business. They intend to sell everything that can be sold; to ship it all by U.S. mail, courier and drone. A dystopia: no more brick-and-mortar stores anywhere. Only enormous, central warehouses, far outside the city limits, lots of security, buzzing with air conditioners, the products they contain ultimately unaffordable.

I long precisely for this: to live in Europe, the continent that bears so much history. The profundity of time, in urban and rural landscapes, legends. The cultivation of farmland and its products. I rarely ate a good meal in the United States. Which, for me, means delicious, quality ingredients.

A kingdom for a ripe melon. A full-flavored tomato. A decent loaf of bread. Salted butter from the cows of Normandy. Olive oil. Ripened cheeses.

It’s a young country, this America. I can taste it. Smell it. Sense it. In the “old world” that I miss, I never felt these things before.

Old World. Deep-rooted traditions. A sense of the profound, developed over centuries and millennia. In the European mentality, landscape, architecture, politics and literature. In the way we deal with things worthy of conservation.

There is a different kind of solidity to the European soul. There has to be a better way to express this. Stability comes to mind. Having a point of reference. Not just a faux presence but one that comes from deep within.

Indeed, America often seems to have a faux presence. Yeah, this is how we do certain things. Modern. Totally. It’s a digital world. Super healthy living. Anyone can be president, even Kanye West (who even hired a campaign team). This is our tradition—but it’s not a “tradition” at all. America has lifestyle and practices. Common grounds and trends. The American Dream.

What it doesn’t have is a presence that extends over thousands of years, the struggle for togetherness. The acceptance of the need for diversity. Cultural history.

The U.S. nation’s foundation extends barely two feet into new, brittle earth. Europe is built on many layers of bedrock with thousands of nuances.

This stability, this depth, is what I miss the most here.

I’m trying to find a way to express it more concretely.

However, I also understand why disruptive markets gain such a strong foothold here.

They embrace destruction because they are unfamiliar with preservation—with preservation and its advantages. Modernity does not always mean smarter or better. Sometimes novelty is only something different or simply crap.

“To connect with people” is important, Deirdre says. It’s not just entertainment. It’s about connections. Any author who seems too distant, too narcissistic, to self-important, too shy, too fearful, will hate these book tours.

It’s all still a jumble in my head. Trump—not Trump. Bookstores. Freezing in air-conditioned rooms. Gluten-free. 25% tips. Huge SUVs. The intensity of the emotions that my listeners manifest to me. Security checks. Uber cars. Poverty—oh, God, the poverty of the homeless. The broken-down healthcare system. The absolutely terrible roads. Really, crappy roads everywhere. Potholes. Cracks. No “downtowns” anywhere. Traffic jams, long taxi rides, airports, upstairs, downstairs, traffic jams again. Half an hour to change clothes. Then on to the next place. Traffic jams. Show time.

Many readers tell me that they weren’t even aware that I’m German—when they read my books, they thought I was French. Or English. I’m not sure what that says about authors writing in German, but I will think about it some more.

9:45 am, local time. I shower. Eat breakfast. My first full American breakfast instead of a coffee, cigarette, bagel and melon.

This is not Trump's land.

This country doesn’t want that man. It doesn’t want him to represent it, to be governed by him. It is discovering the many different forms of rebellion—the sublime to explicit resistance. It is discovering feminism as a political necessity. It is discovering Europe and Germany as role models. It is learning what media can really do. Even Teen Vogue is getting political.

America is discovering itself, or so it seems to me. It is entering the age of a new enlightenment.

By this time tomorrow (6:47 pm European time), I will be back home. It will take my soul a bit longer than that. In September, I’m off to the Ukraine. World, I’m encompassing you.

I shouldn’t cry yet—the tears of overflowing sensation. Porous raw feelings because I travel with all my senses switched on and my emotions switched off.

Just now, I almost succumbed. I’m holding the sob firmly in my mouth.

Coming home.

Home.